Life Goes Online — And Art Goes Digital

Here’s a question: What is art? And what happens to it in a pandemic?

You might be surprised to learn that rather than disappear, it’s exploding! Covid-19 has forced many spaces to close. But artists and museums — in New Haven and around the globe — are creating new ways to make and show art.

Like so much that is happening now, including going to school and hanging out with friends, new art is on electronic screens. It’s called “digital art.” Instead of using materials like canvas, paper and paints, artists are working with digital tools.

“Digital art has been increasing like crazy,” said Marsh, a New Haven artist who works in digital and traditional mediums and spoke with East Rock Record reporters.

Students at East Rock Community & Cultural Magnet School have noticed this art — and found it online. According to The East Rock Record Fall 2020 Survey, 79 percent of students look at art online or through social media. Just over three-fourths said they liked digital art. And 79 percent said that art created and viewed online is “real art.”

Is digital art as serious as “traditional art,” like paintings, drawings and film?

Marsh, who was a student at the old East Rock School, said that “a lot of old-school artists are really annoyed” by digital art and think it is somehow easier. But, she said, “working with digital tools is a lot more difficult than people say.”

Marsh used to be skeptical of digital art, too. “When I first got my iPad, I refused to draw with it,” she said. “Now I’m hooked. There are things I’m able to do with my iPad that I can’t do on paper, or on canvas, because it’s easier to master certain things on the iPad.”

Working digitally, said Marsh has “also made me miss paper. After I used it, I would draw on actual paper, and I started creating really dope stuff.” Marsh added that her canvas work feels more “raw.” She is able to create digital art much more quickly, she said, because she is less fearful of making mistakes.

Traditional art is not going away. But how did digital art and viewing art online become such a big new thing? The pandemic.

In April, museums across the country closed to the public. This included local art and history museums like the New Haven Museum, the Yale University Art Gallery and Artspace. When the state entered “Phase 2” in June, some museums reopened with reduced capacity, sanitation stations, protective equipment for staff and social distancing.

Some others, like the Yale Center for British Art, have remained closed to the public.

“This is my home office,” Courtney J. Martin, the museum’s director, said on a Zoom call. “Every day, I have all my meetings on Zoom or on the phone, but I no longer go into the office.” According to Martin, the only employees who enter the museum are operations workers, like security guards and custodians.

Being closed is obviously a problem for museums. La Tanya S. Autry, a cultural organizer in the visual arts who focuses on social justice, said museums are worried about funding.

“Admission fees are a small amount of operating costs,” Ms. Autry said. “It’s more about who gives money. Because of the pandemic, a lot of donations have been moved to other areas. Museums have to push hard to be competitive.”

But this has also forced museums to be creative, said Ms. Autry, a curator and cultural organizer at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Cleveland, and re-think how they use space. In Cleveland, she is experimenting with art installations that involve sounds and use bus stations and vacant storefronts. She said the pandemic forces museums to think differently.

“What spaces are relevant? What histories happen in those areas?” Ms. Autry asked when she spoke with East Rock Record reporters. Ms. Autry no longer feels comfortable asking artists to travel, so she is thinking more locally.

“Part of being an artist is how well you pay attention to things and understanding the importance of listening to people’s lived experiences.”

In New Haven, many museums moved online. In March, Artspace started Project Zoomie and gave Zoom backgrounds to first responders and let people enjoy art at home. At the Yale Center for British Art (YCBA), Ms. Martin cancelled the museum’s live events and recast them to go online.

“We all had to learn brand-new technology,” Ms. Martin said. “Most of us had never been on a Zoom call.”

The YCBA and Yale University Art Gallery (YUAG) made audio guides for exhibits on mobile apps and social media channels; they made digital archives accessible to the public. The YCBA also started a brand-new series, At Home, with recorded performances and discussions with artists. It has been a hit.

Ms. Martin said that more people from across the world are able to visit the center online than were able to visit in person. The pandemic has also let have “conversations with artists across the world,” she said.

Museums and artists have been forced to experiment. And because digital museums were open while in-person ones were closed, people started debating: Is digital art as serious as “traditional art,” like paintings, drawings and film?

It’s an interesting question. Digital art has gotten popular recently. Apps like Ibis Paint X and Procreate make digital drawing accessible to traditional and young artists.

Many artists, like Marsh, are sharing their art on social media platforms like Instagram and TikTok. Some leave comments on digital artists TikTok pages saying that their digital art is not “real” art. This cause some artists to quit. For example, user859202938582 commented that “digital art isn’t art smh!!!11!11!” which may bring down an artists’ motivation.

This discussion is different for other art forms. Music can be heard, so the “digital” experience of listening to music is very similar to live music. And “cosplay” art is a kind of performance costume art that is worn. Clothing artists don’t have to worry about making their costumes digital. So people don’t often say the online versions of these art forms are not real art.

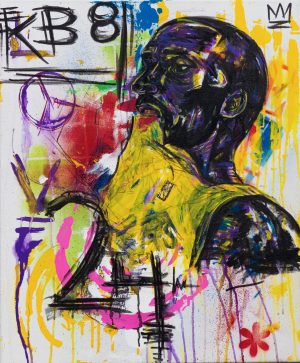

Artists have not just moved online. They also moved into the streets to protest for social justice — and made art that reflects this activism.

The death of George Floyd, who was handcuffed and pinned to the ground by Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin, sparked protests against police violence across the country, and conversations about racial justice. There were protests in New Haven in late May and early June. Soon after, local artists created a Black Lives Matter mural on Temple Street, beside the New Haven Green.

Marsh painted the “M” on the mural, which is full of flowers. As an artist, she wants to drive conversations about social justice. Even though reality “can look pretty sucky,” she incorporates current events into her artwork. “I want my art to evoke feeling, whether you think it’s beautiful or it disgusts you,” she said.

Art, said March, should evoke emotion and touch “a different part of you that reading or hearing can’t always give you.”

For Monica Ong, a visual poet based in New Haven, art is about using several mediums — digital art, social justice and poetry — to evoke emotion in her audiences. In July, Ms. Ong published an audio poem for two voices called “Yellow Insomnia.”

She performed it with Randall Horton, a University of New Haven professor who is Black. It is about how both Asian and Black communities can support Black Lives Matter. Ms. Ong wrote the poem after asking herself how she could use art to help her fellow citizens.

“How can I deepen my commitment to shared humanity?” Ms. Ong asked. “Part of being an artist is how well you pay attention to things and understanding the importance of listening to people’s lived experiences.”

The pandemic is changing art. It is changing what art looks like, how we look at it and what it is trying to tell us. That is exciting. There is a lot of pain and hardship. But for many artists, that is also what helps them to create.

Edited by Rianna Turner