New Haven Working to Welcome Record Numbers of Afghan Refugees

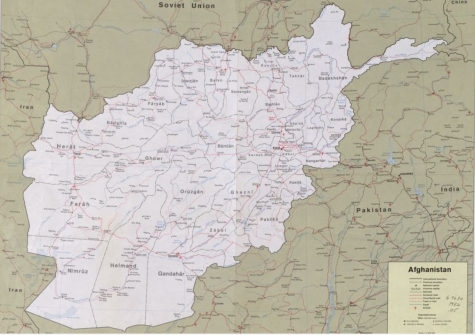

Last August as the whole world watched, thousands of people from Afghanistan tried to leave their country. Children and parents were afraid to walk in the streets when the Taliban took over the capital of Kabul.

Now, many months later, New Haven is welcoming a record number of Afghan refugees who fled. The process of resettling people has just begun.

As a sanctuary city, New Haven has a history of welcoming immigrants and refugees. The Integrated Refugee & Immigrant Services (IRIS), which began as the Interfaith Refugee Ministry in 1982, has been helping immigrants settle in New Haven for 40 years.

But Chris George, the executive director of Iris, said the influx of refugees has been the largest the organization has resettled, “by far.”

He said the U.S. Department of State asked them to welcome 400 Afghans in October, November and December alone. “This is much more than we normally welcome in one year,” he said. As a result, Mr. George said, IRIS has increased from 50 to 80 employees.

IRIS has also needed more donations, volunteers and local support. Mr. George said the community response has been “amazing.”

Students at East Rock School are eager to have Afghan classmates. According to the East Rock Record Fall 2021 Survey, only about one-quarter of students at East Rock Cultural & Community Magnet School reported knowing someone from Afghanistan. But 71 percent said they look forward to having classmates from there.

“I think it would help with diversity and bring awareness,” said fifth grader Charlotte Martinez. “I would like to hear about their culture and stuff. I have never been out of the country and it would be great to hear about another country.”

Ann O’Brien, director of community engagement at IRIS, said that the refugees left Afghanistan quickly and arrived with little.

“When they come to us, they just have like one bag of clothes because they had to leave their homes really fast, like in a day,” she said. “So when they get here, we provide them with all of the food that they need. We find them a house. We bring them to a place to get clothes.”

IRIS also helps the adults find a job to begin earning money. For children, coming to a new place and in many cases not knowing the language also makes it difficult, said Ms. O’Brien.

Students who arrive also register for school. But language differences can make this a struggle. “We give tests to see if they speak English,” said Daniel Diaz. Students are then often placed in bilingual education classes, depending on their level of English. In many cases, he said, students have to start fresh learning a completely new language.

Ms. O’Brien said that is one of the biggest challenges. “The majority of these children who were evacuated do not have any English,” she said. “They were not learning English.”

A few words: “Hello” is “salaam”; “goodbye” is “khoda-afiz”; “please” is “meera bani;” “thank you” is “manana;” “help” is “marasta;” “I am sorry” is “bakhana ghwaram.”

Despite the challenges, Ms. O’Brien said they try to be upbeat. “The more fun we make it for them, and the more friendly we are in a kind of a low-key way, the easier it will be for them,” she said.

Some Afghan students’ fathers do know some English, said Ms. O’Brien. “They might have worked for the U.S. government,” she said. “But the majority of the mothers and the kids won’t know any English. And so, they’ll need everybody in New Haven and all the other towns to just be really patient with them. It’s going to be exhausting for them.”

There are many emotions that also affect how new arrivals feel, she said. Americans may have bombed their homes or hometowns. She said some may want to be friends. Others may be shy; still others will want to play.

One of the biggest challenges is housing. “For each family, we have to go out and find one apartment and all these families are different sizes,” Ms. O’Brien told East Rock Record reporters during a Zoom interview.

“Sometimes it’s just a mom and a dad and one little kid. Sometimes it’s a mom and five little kids.” She said they estimate needing about 250 apartments. IRIS has also already found houses for some families.

In an email appeal sent in November, Arzoo Rohbar, an IRIS case manager who was once a refugee, recalled that “The first thing I remember is waking up in the morning and how comfy my bed was. The house was set up for us. It was small but really beautiful. It just felt like home.”

Many people are trying to help. Jim Ancil, who started working with IRIS as a mover in 2017, when former President Donald Trump banned travel from several Muslim countries.

“For years I helped on a volunteer basis. I helped refugee families move from one house to another,” Mr. Anctil said. “But the fall of Kabul created a wave of people and numbers that IRIS has never had to deal with before. Now they pay me as a subcontractor, and we’ve been able to do quite a bit more than we have in the past.”

“It’s the largest number of people that IRIS has had to deal with in this short a time,” he said. “But IRIS right now has more funding, more volunteers, more donations than they’ve had in many years. It’s a different organization right now than it was a year ago.”

The speed of the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan affected people in New Haven, said Mr. Diaz, the public school liaison. He got calls from upset families who were caught overseas. “They had gone there in the summertime and they got stuck in Afghanistan,” he said.

Ms. O’Brien said in October that IRIS was trying to help at least three families return to New Haven. At the time, she said about 200 organizations like IRIS in different cities across the U.S. were facing the same struggle.

“We know there are other Afghan families in all 200 of those cities that also went back to Afghanistan at the beginning of the summer,” Ms. O’Brien said then.

Kirsten Hebert, who teaches third grade at East Rock School, previously taught at Barnard Environmental Studies Interdistrict Magnet School. Barnard has welcomed the largest number of students from Afghanistan of any New Haven Public School, said Justin Harmon, spokesperson for the district. Even before the recent arrivals, Ms. Hebert said Barnard had already had students from Afghanistan, which gave her a chance to learn about the culture.

“I’ve learned about different holidays and different food traditions,” she said. Having more students from Afghanistan in the classroom is good because, said Ms. Hebert, “the amount of learning that goes on benefits both sets of kids, the kids that are arriving and the kids that are in the classroom. A lot of learning goes on there and I think it’s wonderful and I hope we do get together.”

If more students do arrive from Afghanistan, how should people prepare? Ms. Hebert said that she would welcome them, “the same way that I do any new kid who comes into my classroom: have their desks all ready and all set up, read a special story about new kids coming to the class, make sure that my class understands that someone new is coming.”

Edited by Rachel Calcott.