Imagine flying a plane. Then imagine flying it straight into a hurricane. On purpose!

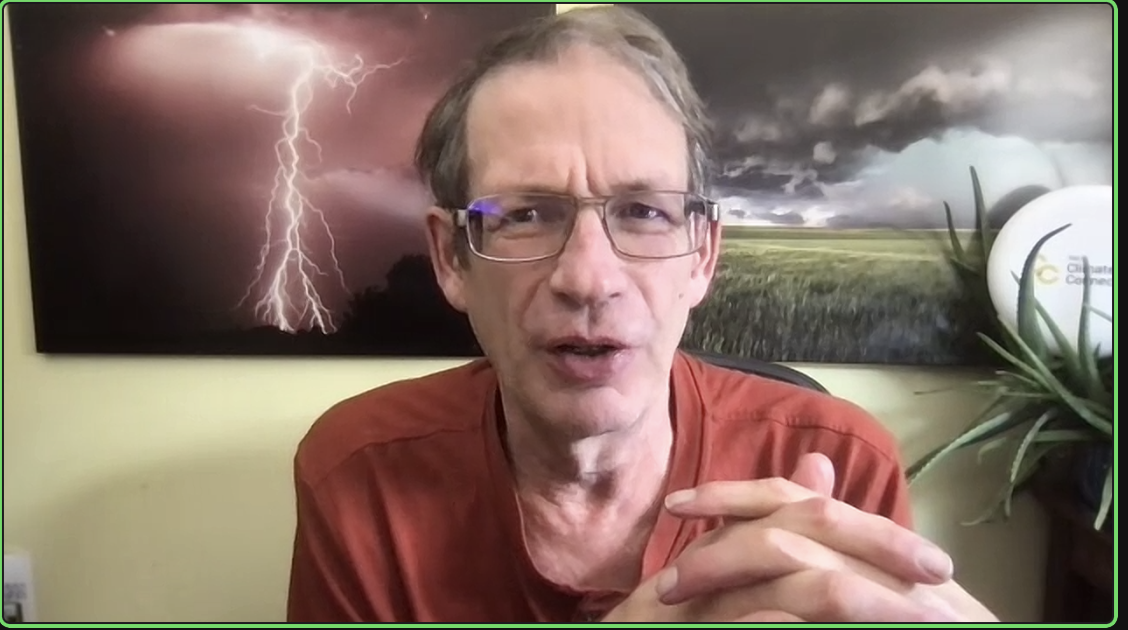

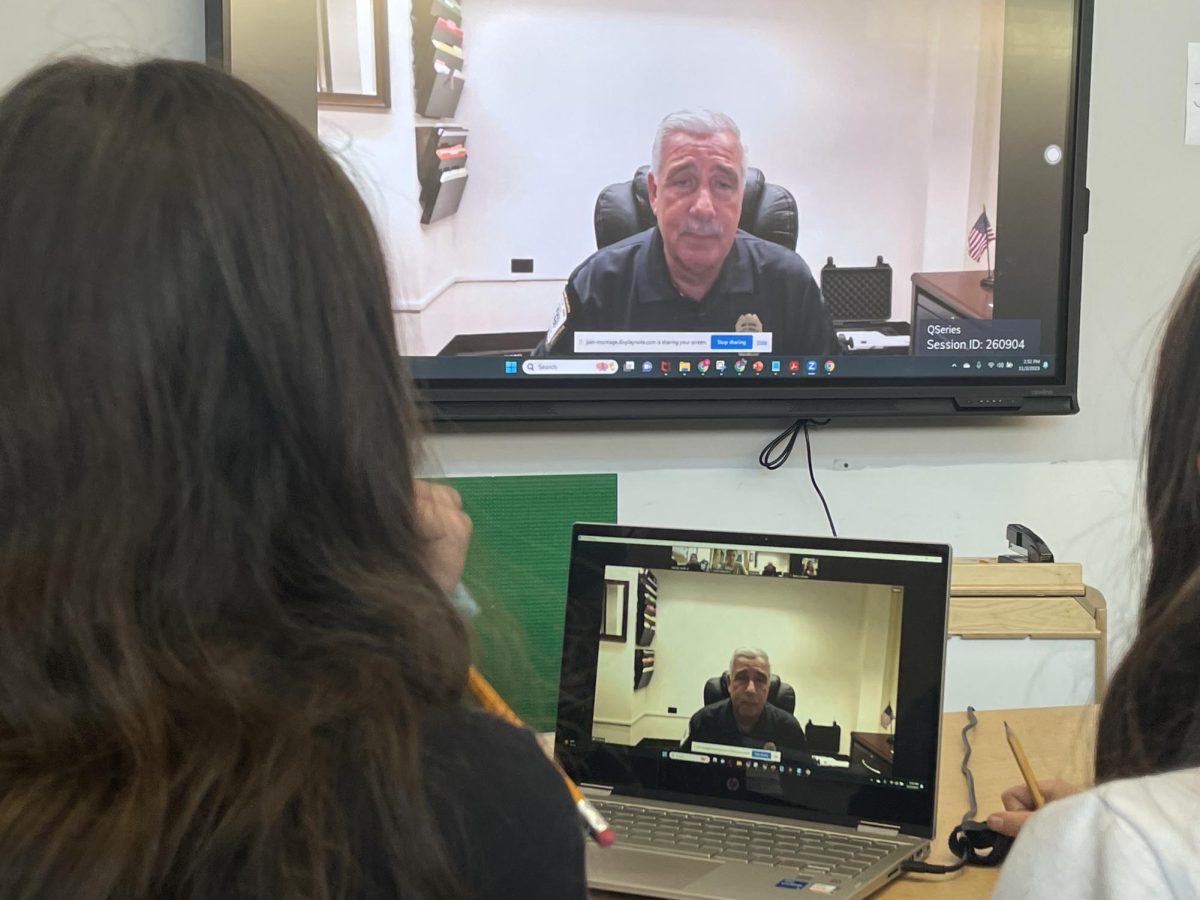

If this seems incredibly scary and dangerous — it is. But it is what Jeff Masters, a meteorologist for Yale Climate Connections, the co-founder of Weather Underground — and a member of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Hurricane Hunters team — did for a job.

Mr. Masters, who was part of the storm chasing team from 1986 to 1990, told East Rock Record reporters about his perilous flights and fantastic stories. He said that hurricane hunters fly into storms to take measurements to share with forecasters.

“The reason we fly into hurricanes is to get a better information about the intensity” of the storm, he said, adding that “satellites can’t see through a cloud.”

That information helps people on the ground better forecast and prepare. During his career, Mr. Masters flew into two Category 5 storms with wind speeds of 157 miles per hour or higher. (Category 1 storms are the mildest and Category 5 are the most intense.)

In the middle of the eye of a hurricane, he said, “it is gorgeous. It is like you are in stadium, surrounded on all sides with white clouds with the sun shining through or, at night, the moon.”

Mr. Masters described how hurricanes form. He said there were three necessary things to kickstart an intense storm: (1) warm ocean water, (2) some pressure to get it spinning, and (3) plenty of moisture in the atmosphere. He noted the pressure typically comes from cold fronts on the East Coast of the United States.

Mr. Masters said that from the perspective of a hurricane hunter, storms have different parts. The eye of the hurricane sits at its center. It’s also the calmest weather area in the hurricane. Masters said that it is usually beautiful and quiet in the eye. “Sometimes, you see lightning. If you look below, you can see the ocean. Sometimes it’s calm. Sometimes there are 40-foot walls.”

The eyewall of the hurricane, he said, is the most dangerous area. Flying through it, he said, requires traveling into “a circular ring of intense thunderstorms where the worst turbulence, heaviest rains, and strong winds from ground to atmosphere occur.”

Even though the flights sound terrifying, Mr. Masters said that “only one out of five hurricane flights was a white-knuckler.” During an interview, Mr. Masters said that his most memorable flight was into Hurricane Hugo on September 15, 1989. It was a Category 5 hurricane. But, he said, his team had mistakenly thought that the hurricane was a Category 3 level before they flew into it. He said their plane shot up and down as the draft carried them all over in a terrifying loss of control. The engine even caught on fire! The pilot lost control, and they dove toward the ocean until they gained control 900 feet from the water!

After such an intense experience, reporters wanted to know: Why would Mr. Masters choose such a dangerous career? He said that growing up in the Midwest, he always found weather interesting, but wanted to study the most exciting weather, which led him to hurricanes. Mr. Masters said a hurricane hunter’s main job is “to get a picture of the intensity of a hurricane.”

On the ground, people may need to evacuate areas that can be hardest hit by the storm. Mr. Masters said many people do not know where evacuation routes are located. “If you’re familiar with hurricanes, then yes,” he said. “But if you are not used to the storms, no.”

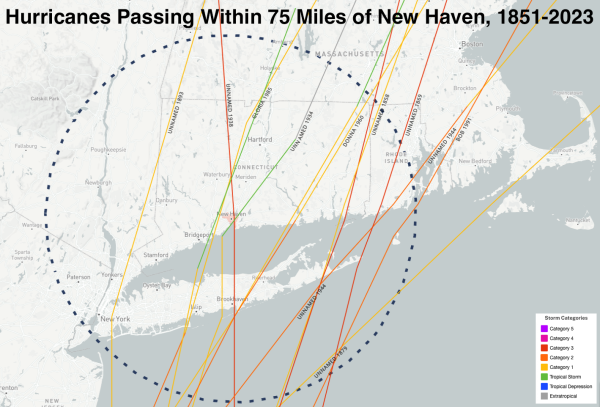

But people may want to pay more attention. Mr. Masters said that global warming may pose dangers for people in New England as air and water temperatures rise.

“It’s likely Connecticut will see more storms,” he said, adding that in addition, “any storm is going to get more rain because a warmer atmosphere holds more rainfall. Storm surges will also go further inland with rising sea levels. More hurricanes can equal more damage with people affected differently. During Hurricane Katrina, he said, “people with cars evacuated before others.”

Hurricanes also do a lot of damage to property. In 2021, Hurricane Henri caused $700 million damage, and three more hurricanes occurred that year: Hurricane Elsa in July, Hurricane Fred in August, and Hurricane Mindy in September.

With these scary statistics and the anticipation of worse hurricanes, students were left wondering what the future holds for hurricane hunters. Mr. Masters said that he “used to tell people that the most dangerous part of my day was driving to work” — that is, until he flew into Hurricane Hugo. “That was by far the most intense experience of my career.”

Edited by Hollis Long